Raphael Bostic

President and Chief Executive Officer

Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta

Annual Meeting of the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association

October 19, 2020

- Atlanta Fed president Raphael Bostic is speaking to the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association about how the economic recovery benefits some parts of the economy much less than others.

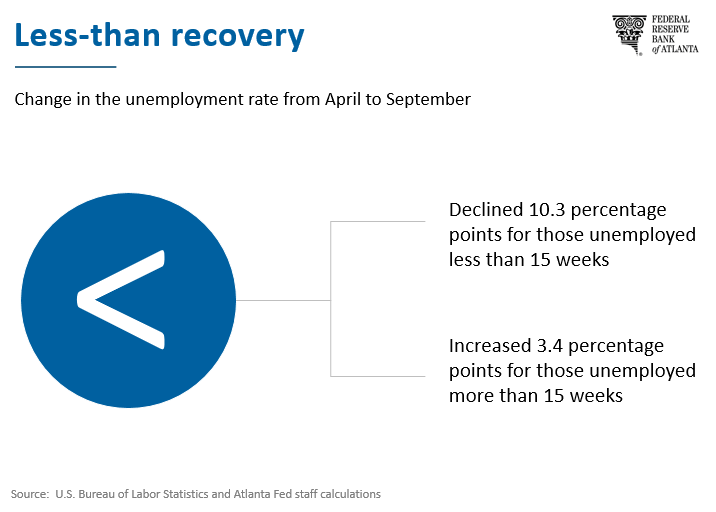

- Bostic said he and his macro team have turned to a mathematical symbol, the less-than sign, to describe the present conditions as characterizing a "less-than recovery."

- Bostic pointed out that while parts of the economy and the population are prospering, moving on an incline, a considerable portion is moving in the opposite direction, as represented by the descending leg of the less-than sign.

- He said that these circumstances are laying bare—and exacerbating—disparities that have long plagued our economy, along ethnic, racial, gender, geographic, and occupational lines. The Fed must participate in a deeper, more creative reckoning with a history of racial injustice that continues to weaken the economy for all of us.

- Turning to monetary policy, Bostic said the Fed's new approach should help minorities, women, and lower-income earners be more fully connected to the labor market.

- He is comfortable with the Fed's current policy stance but wants to be clear that once we are past the current crisis, he will heartily support the removal of the Fed's emergency vehicles.

- Bostic said that he and his colleagues will work to make sure the Federal Reserve is a place that people look to for thoughtful solutions to issues around racial equity and historic disparities.

Thank you, Ken, for the kind introduction and thanks for inviting me to visit with you.

It's a pleasure to address the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association. I think it is wise that you have chosen to focus your annual meeting on the myriad unknowns associated with this public health crisis, which has spawned a deep and unprecedented economic crisis. In my remarks today I will talk a bit about what I am seeing in the economy, and I hope this can demystify some unknowns, or at least help us to consider them in more productive ways.

Before I delve into the substance of my talk, please keep in mind that these thoughts are strictly my own. They do not necessarily reflect the views of my colleagues on the Federal Open Market Committee or at the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta.

Over the past few months, you've heard economists and analysts use a multitude of letters: V, U, L, W, and so on. Well today, I'm not going to do that. Instead, being economists, my macro team and I turned to a mathematical symbol—the less-than sign, and I've come to describe the present conditions as characterizing a "less-than recovery."

In my remarks this afternoon, I'll explain what I mean by this and explore some of the implications of an economic recovery that benefits some parts of the economy much less than other parts. In short, these circumstances are laying bare—and exacerbating—disparities that have long plagued our economy, along ethnic, racial, gender, geographic, and occupational lines.

I will also discuss what the Federal Reserve and particularly the Atlanta Fed can do and are doing to confront these disparities, before closing with thoughts on how the finance and economics field might grapple with these challenges in a more meaningful way.

While the aggregate numbers can be interpreted as promising, I believe they mask the fact that the recovery is progressing in a pattern that, when graphed, looks to me like a less-than sign.

Let me explain. There are parts of the economy and the population that are prospering, moving on an incline. Most college-educated people and professionals who can work remotely along with sectors like home improvement chains, grocery stores, online retailers, and others are doing well.

Some commentators have even gone so far as to proclaim the COVID recession effectively over for many of those who didn't lose their jobs or could easily shift to working from home.

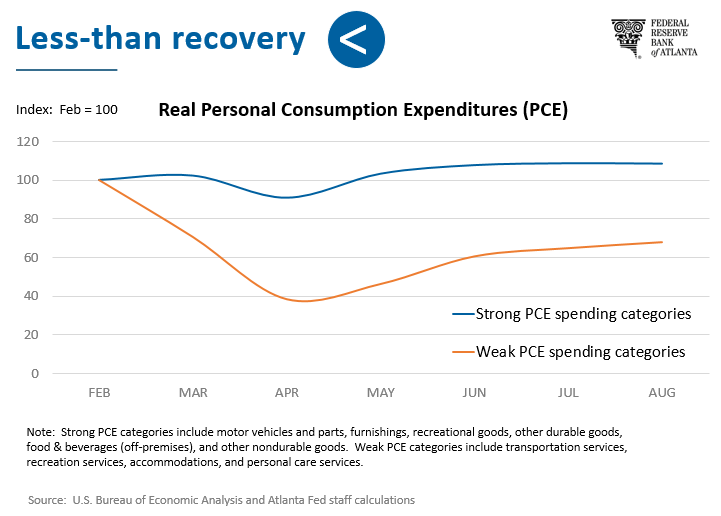

Unfortunately, that's not the whole story. A considerable portion of the economy and population is moving in the opposite direction, as represented by the descending leg of the less-than sign.

This group includes industries that depend on people crowding together, such as restaurants, hotels, recreation, household care services, transportation, tourist attractions, many small retailers, and the people who work in those sectors.

These industries saw economic activity decline as much as 80 percent in the first two months following the pandemic. Through August, their business output remained 50 percent below pre-COVID levels. Employees in those industries are primarily lower-wage workers and disproportionately people of color, younger people, and women. In other words, the people who are often least equipped to weather a prolonged bout of unemployment are bearing the brunt of this health crisis and economic downturn.

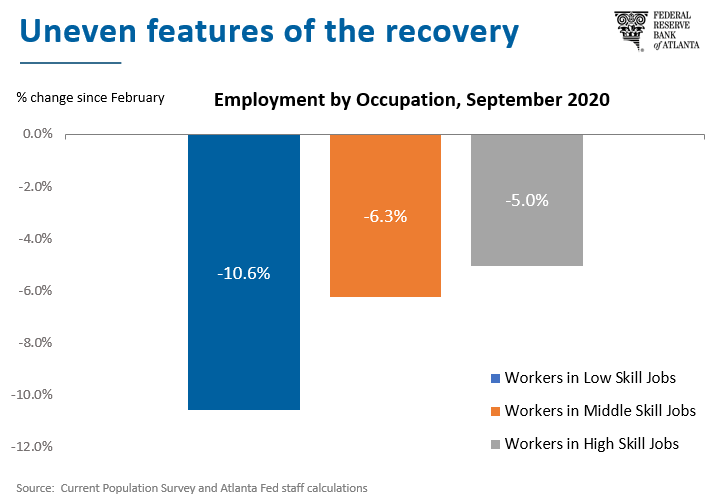

In this context, it is useful to look at what has happened to jobs with similar skill requirements. For this, I will use a classification scheme for low-, middle-, and high-skill jobs made popular by MIT economist David Autor and his coauthors.

Workers in low-skill occupations, many of which are in service-oriented industries such as food preparation, cleaning, and hospitality, accounted for 17 percent of total employment in February. But they suffered double that percentage (33 percent) of the share of jobs lost between February and April.

This is notably different from the typical recession triggered by an economic shock. The typical downturn has generally affected sectors such as construction and manufacturing, which employ mostly middle-skill workers. For example, in the Great Recession, nearly all of the job loss was concentrated among middle-skill workers, while employment for low-skill jobs (in service-oriented industries) actually kept growing.

Equally troubling, many of the jobs lost in the sectors that comprise the declining portion of the less-than sign may not come back. Segments like business travel and food service might not recover for years. This assumes, of course, that they will at some point return to their pre-COVID state. But this is not assured. Take restaurants. Some contacts in the food service industry are expecting a permanent contraction of up to 20 percent of restaurant capacity. Moreover, the restaurants that do survive could more intensively deploy labor-eliminating technology, such as electronic tablets customers can use to place orders, and take other measures to minimize close human contact.

As another example, a hospital director told me they are seeing nearly a third of patients via telemedicine, compared to just 3 percent before the pandemic.

Those kind of developments could have profound labor market implications for the numbers of jobs and the types of skills employers will require. For instance, the hospital may require fewer orderlies but more nurses trained in using telemedicine technologies. Further implications? Consider that the hospital hosting fewer in-person visits might scrap plans for a new parking deck. That's a number of potential construction jobs that would not be realized.

Overall, only half the roughly 22 million jobs lost in the first couple months of the pandemic have reappeared.

Already, the data are warning of these kinds of structural shifts in the labor market that, absent the pandemic, may have taken several years or a decade to unfold. Job losses listed by the Bureau of Labor Statistics as permanent, according to its household survey, rose from 2.3 million in May to 3.8 million in September, on a seasonally adjusted basis. This increase in long-term unemployed individuals has happened in about six months. It took over two years for a comparable shift to occur following the Great Recession. The pandemic has been a big accelerant.

More sobering still is that, if we assume that jobs continue to be added at the pace seen in the September labor report, it will take an additional 16 months to return to February employment levels. And that does not account for the additional employment growth needed to keep pace with population growth. The upshot: if September is our new jobs baseline, we will not return to pre-COVID total employment levels until December 2021.

Widespread permanent job loss could become a material risk to the recovery. The data on this are clear: permanently laid off workers find it far more difficult to rejoin the labor force. This would make recovery more difficult to sustain.

We saw that dynamic in play not long ago. It took years for masses of displaced workers to learn new skills necessary to find work in entirely new fields after the Great Recession.

That said, the prolonged economic expansion eventually created job opportunities for marginalized groups and generally strengthened families, businesses, and communities. Unfortunately, many of the people who were last to benefit from the gradual recovery from the Great Recession were the first to suffer at the onset of the COVID recession.

What the Fed can do

As policymakers, our goal should be to ensure that their suffering does not become permanent lest the recovery take far longer. Indeed, an unnecessarily slow labor market rebound could just drive historic wedges deeper, continuing to exacerbate the geographic, racial, gender, and income disparities in our economy.

By traditional lights, it might appear the Fed is ill-placed to address long-standing economic inequities like income and wealth gaps. After all, these disparities are similar to gaps in access to quality health care, housing, education, and job training. In this context, I'm of a mind with my Boston Fed counterpart, Eric Rosengren, who recently pointed out that we must think about these inequities holistically.

Admittedly, the Fed cannot make grants and put money directly into the pockets of those families and small businesses that need it most. We are not directly involved in health care and education. Fiscal policymakers clearly have a significant role to play in ensuring that the economic disruptions don't become deeply rooted, that the wedge does not continue to widen these disparities.

Still, the Fed has an important role to play. We must be central to this conversation. And increasingly, I think we are.

Let me mention a few ways our bank is attacking these problems. First, we're going micro, because conditions vary greatly across places and populations.

At the onset of the coronavirus pandemic, we, along with our Federal Reserve System colleagues, stepped up efforts to survey localities about how they were doing amid the slowdown—the intensity of the problems and how long leaders in the government, business and nonprofit sectors anticipated full recovery would take.

Those findings paint a picture of low-income, minority, and rural communities suffering disproportionately and anticipating longer recoveries. In April, just about half of the people we surveyed said the economic downturn would be over in September. That consensus has steadily extended into 2021 and, for many contacts, into 2022.

We are using those findings to inform a more muscular outreach program. We are going micro in our outreach by advising local government officials on ways they might help businesses in their communities. In this vein, we've been talking about how you maintain business activities in the time of COVID.

We're trying to help the philanthropic sector understand the stresses on their constituencies, and suggest ways they can make a meaningful difference in the communities they serve.

Our bank also is researching and working to dismantle barriers to career advancement for low-wage workers. One effort we're making is helping workers better understand benefits cliffs. These happen when someone acquires new skills and earns, say, an extra dollar an hour, but because public benefits are automatically reduced as wages rise, this person actually loses the equivalent of $3 or $4 an hour in supports and ends up worse off, for years in many cases, by trying to better their circumstances.

Taking research from the lab to the real world

We are taking our benefits cliffs work from the laboratory to the real world, where it can improve the lived experience of real people. Our researchers and outreach folks have established more than a dozen partnerships across the country to build practical tools for state agencies and other groups to help these workers address what amount to exceedingly high marginal tax rates for some of the lowest paid workers. We are working with the state and other nonprofit organizations in Alabama, Louisiana, Florida, and Georgia in our district, as well as in Connecticut and Oklahoma, among other places.

At the Atlanta Fed, we have also established a research and outreach team focused on workforce development. The aim is to equip workers with the skills they need for not only the jobs of today, but also the jobs of tomorrow. As I noted, the pandemic crisis is accelerating a tectonic shift in the labor market, and, simply put, too many workers are not ready. In response, we recently worked with the Markle Foundation and others to stand up the Rework America Alliance, which is aggressively moving forward with partners across the nation to reorient the existing job training infrastructure so it can help more workers be prepared for these changes.

Across the Fed System, we are also using our convening power to confront the immediate effects of the COVID downturn and the ongoing effects of historic economic disparities.

We have joined the Boston and Minneapolis Feds to present a seven-part webinar series on racism and the economy. If you didn't catch the first installment this month, I recommend that you look it up, and I encourage you to watch for upcoming segments on topics including education, housing, and wealth and financial services. You will hear views expressed that you are not accustomed to hearing in a forum affiliated with the Federal Reserve, I assure you.

Ultimately, that's the point. We need to participate in a deeper, more creative reckoning with a history of racial injustice that continues to weaken the economy for all of us.

Now let me turn to what you probably expected to hear from me—monetary policy. Our monetary policy stance today is a far cry from where we were just eight months ago, when we were enjoying the fruits of a historic expansion, with inflation approaching our 2 percent target and record low levels of unemployment spurred by many people less attached to the labor force finding jobs. The pandemic changed all of that, triggering bold and decisive action on the part of the Federal Open Market Committee to provide support to the economy and ensure that financial markets continued their smooth functioning.

We quickly reduced the fed funds rate to effectively zero and, with unprecedented swiftness, stood up a series of facilities designed to provide support for targeted financial markets that were showing signs of extreme distress.

These proactive actions, I am pleased to say, were quite effective. Spreads in many financial markets backed off their extreme levels soon after the facilities were deployed. In some cases, like the corporate bond market, the easing occurred without a significant draw on the facilities, indicating that simply the presence of a backstop vehicle was enough to reduce fears.

I would like to say a few words about a number of these facilities. Some, like the Municipal Loan Facility and the Main Street Lending Program, represent totally new ventures for the Fed and have required a great deal of learning on the fly. As we gain a deeper understanding of the needs and nuanced circumstances of the targeted sectors, we will continue to reshape these facilities to maximize their effectiveness.

On balance, I am comfortable with our current policy stance. As I have detailed today, though the U.S. economy continues to show clear signs of recovery, there remain significant portions where the recovery has been weak or nonexistent. That reality tells me that it will be some time before we tighten our interest rate stance or pull back strongly from our actions supporting financial functioning.

That said, I want to be clear that once we are past the current crisis, I will heartily support the removal of these emergency vehicles. There should be no expectation that these will persist in a new steady state.

Though there has been considerable focus on emergency measures through much of 2020, the Committee was also able to complete its multiyear review of its longer-term policy framework. Most of you likely are well aware of our August announcement of a fundamental shift in the Fed's monetary policy framework.

There are two parts to this that I would call out as particularly noteworthy. First, the new framework makes explicit my long-held view that levels of inflation above the 2 percent target can persist for a time without being a cause for concern. What concerns me more are trends relative to the 2 percent target. If we are somewhat above 2 percent, but the level is stable, I will likely not be concerned. By contrast, if we are somewhat above 2 percent and the distance between actual inflation and our target is increasing steadily, that would be a reason for concern and merit a policy response. I think this is a commonsense approach to managing our inflation target.

The second important aspect has been summarized in the press as a "lower, longer" approach. Boiled down to its essentials, this codifies that the FOMC will no longer seek to preemptively blunt runaway inflation by tightening monetary policy when unemployment reaches certain low levels. The disparities we're discussing today played a large part in this strategic shift.

We are committing to let the economy grow a little more robustly than we might have otherwise because we have learned over the past decade that even historically low unemployment is less likely to spark troublesome inflation. Importantly, then, the new framework calls for policy to support "broad-based and inclusive" job gains. And it states that policy decisions will be based on estimates of "shortfalls of employment from its maximum level"—not "deviations."

This is no small matter.

A significant cost of tightening monetary policy prematurely during an economic expansion is that it can block job opportunities from reaching all communities. Our new approach should help minorities, women, and lower-income earners to be more fully connected to the labor market. That will give those traditionally marginalized groups a better opportunity to secure jobs and economic resilience, which for too many of our citizens has been severely tested by the COVID economic downturn.

Of course, the Fed carefully weighed numerous factors in crafting the new long-run policy strategy. We have been criticized at times for not listening enough, particularly to Main Street. Therefore, we conducted events across the country to seek public input as we refined our policy approach. One clear message we heard before the pandemic from community, labor, workforce development, and business leaders across the country was that the strong job market was particularly beneficial to low- and moderate-income communities.

We are going to keep listening because we have far to go to dismantle entrenched disparities that act as a yoke on the nation's economy. One more snapshot of current conditions makes this abundantly clear.

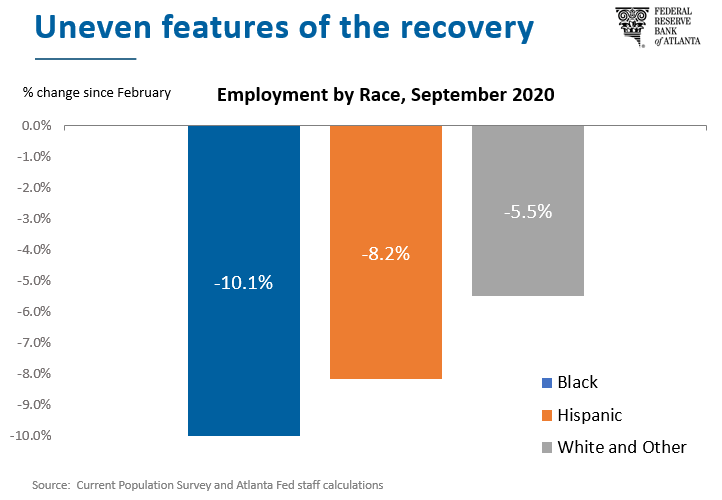

Across the jobs spectrum, minorities, particularly African Americans, are bearing an outsize burden of employment losses. A much larger share of Blacks and Hispanics (22 and 23 percent, respectively) than whites (13 percent) worked in low-skill occupations before the pandemic.

So not only are those individuals and families absorbing the sharpest blows from job losses, but they have also experienced a much slower employment recovery than whites in similar low-skill occupations. What's more, this disparate impact is not confined to low-skill occupations. There is also a notable difference in employment outcomes for Blacks in high-skill occupations in industries less damaged by the pandemic.

Making a commitment to an inclusive society

In sum, the speed and the magnitude of this punishing economic crisis is falling disproportionally on those least equipped to handle it. And for many of these individuals and families, government support has evaporated. That could leave millions of our fellow citizens in dire straits. We are seeing some unfortunate evidence that this may be happening already. Evictions in the metropolitan Atlanta area began to rise significantly soon after moratoriums on them expired in July.

As a nation, we cannot afford to continue leaving talent, productivity, and creativity on the table. So we as a society, and I'll aim this call to the economic and financial fields in particular, must make a commitment to an inclusive economy.

The fields of economics and finance must acknowledge that the influence of race is multidimensional and lasting. If we are to build a more equitable economy and financial system, the people who build it need to know and appreciate the history of our system. Too many people, in finance and among the general public, are unaware of the role financial institutions, policies, and structures have played in calcifying inequities in our economy.

Indeed, much financial research has ignored race and other demographic differences in the population. Partly as a result, this is an area ripe for research, product innovation, and policy proposals to help eliminate barriers, reduce frictions, and create structures and institutions that support the success of all Americans.

Only by investigating differences in behaviors and the practical effects of policy can we recalibrate our approaches or devise wholly new strategies to help everyone engage and thrive in the economy. For instance, in a new paper, one of our research economists, Kris Gerardi, and two coauthors suggest that Black and Hispanic Americans basically overpay for mortgages compared to non-Hispanic white borrowers. This appears to happen mainly because Black and Hispanic mortgage holders do not refinance as often as non-Hispanic whites do when mortgage interest rates decline. Thus, they end up continuing to pay higher rates than they would otherwise. Precisely why those mortgage holders refinance less often is unclear. It may well not be exclusively rooted in raw discrimination, to the extent that this plays a role at all.

The point, though, is that this type of work highlights differences in behavior that are salient for pricing securities and providing financial advice. Just as important, the work offers ideas about structural changes to mortgages that might mitigate the disparities, which could help millions of our fellow citizens pay less for mortgage loans, and therefore have more disposable income.

Clearly, the challenges here are considerable. Still, I'm optimistic. Why? For one, we are having these conversations. I don't think that would have happened even six months ago. By itself, the willingness to discuss these matters shows me there is an appetite for change and, maybe more important, a willingness to work to make change.

My colleagues and I are going to work to make sure the Federal Reserve is a place that people look to for thoughtful solutions to issues around racial equity and historic disparities. I hope you see the value of this virtuous pursuit and join in the effort.

If we succeed, we can create a more perfect union that in fact, and not just in words, allows for unburdened life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness for all citizens.